I.

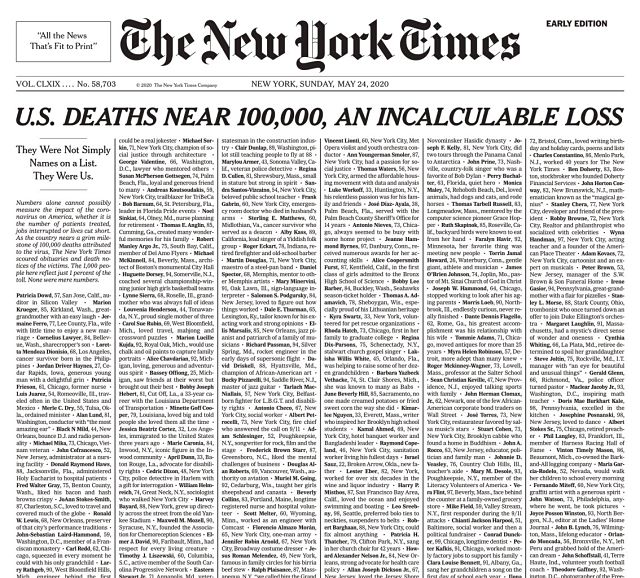

I want in this post to clarify some muddy thoughts I have about infection, hedonism, and public health. I’ll start with HIV, why not. You may have seen the by now iconic front page of the NY Times listing just some of the names and bio data of the nearly 100,000 people killed by SARS-CoV-2:

Compare that cover to the same paper’s coverage of the milestone hit, in 1991, of 100,000 deaths from AIDS in the U.S.:

If you can’t see, that’s page 18 of the front section. Also, the Times didn’t bother to write or report its own story, deciding instead to run an AP wire report—the journalistic equivalent of a retweet.

If you’re a Times editor, or the sort of person who likes to win arguments so’s to stop feeling uncomfortable, you might point out that 100,000 deaths in three months is much more alarming, frontpage-style news than 100,000 deaths over the course of eleven years. You might even make the more dangerous argument that CoV-2 affects everyone, whereas HIV, at least in 1991, affected mostly gay men, a small minority of the (newspaper-buying) population.

I’m going to return to that second argument. All I have to say for the first is that what broke this weekend (and in 1991) was not news, but hearts. That 100,000 (almost) have died is data anyone can access at any time. The point of the litany of names on the cover was to mark an occasion, to send a message, to highlight some severities regarding this virus that seem to have been overshadowed in the recent weeks. It’s a memorial, and the Times was so proud of the good job they did they even published a piece about how they came up with it.

Which means that 100,000 AIDS deaths weren’t worth memorializing in the paper.

II.

I might try to answer the question of why. Homophobia seems an obvious answer, and so does a fear of sex. That HIV is (mostly) transmitted through sexual contact makes it a virus some want to moralize about. If you hate sex and hear about someone’s infection, it’s extremely easy to think Well, that’s what you get. Which might be why the Times felt 100,000 AIDS deaths was merely reprintable news, and not “incalculable loss.”

Which is to say the loss we feel has something to do with innocence, and with this virus’s lack of discrimination in who it infects. Those 100,000 appear as victims of some unfortunate event. But it’s important to remember that no virus discriminates.

Also worth pointing out is that CoV-2 has become no less moralizable a virus than HIV, with lots of public debate about what’s healthy/unhealthy behavior, and thus good/bad behavior, and thus who among us gets the label of good/bad pandemic citizen. We’ve all seen mask-shaming posts about people in parks, and we’ve seen “No Masks Allowed” signs posted at brazenly re-opened business. Maybe you saw that pool party at the Lake of the Ozarks on Memorial Day weekend, and maybe that image made you feel something very strong and impassioned.

We are a nation judging each other over our behavior. The virus has put us in moral positions. My grandmother is not expendable, etc. Being on the right side of a moral debate feels very good, much better than, say, a policy debate, because you know that you’re on the side of humanity, the very goodness within all of our hearts. And in the loneliness of staying home, what could be more necessary than feeling righteous with each other?

I feel within my good heart that moralizing any virus is a no-win position, and I hope by the end of this to solidify why.

III.

Let’s go back to the argument that AIDS is a “niche” disease. Another one used to be syphilis, and I find the connections Leo Bersani finds between the discourse around these viruses especially useful in thinking about the moralism of our current viral moment. 19th-century Victorians villainized sex workers (and not so much the men who hired them) for spreading syphilis, and Bersani points to how much of that villainy lay in the apparent vice of gluttony: “Prostitutes publicize (indeed, sell) the inherent aptitude of women for uninterrupted sex.”

Victorians contrasted this to (presumed) satisfied procreative marriage sex, while Bersani likens this to the potential in gay anal sex for multiple orgasms with multiple partners, and the ready role-switchings of insertor to insertee. In short, amid all the Puritanical restrictions on sex we seem to have one involving number of sex partners per day. (The question is whether this restriction would be in place within an STI-free universe, and given the primacy that pregancy/procreation holds in our sex discourse I have a hard time believing it wouldn’t.)

So promiscuity is the problem, in this mindset, not any virus:

The realities of syphilis in the nineteenth century and of AIDS today “legitimate” a fantasy of female sexuality as intrinsically diseased; and promiscuity in this fantasy, far from merely increasing the risk of infection, is the sign of infection. Women and gay men spread their legs with an unquenchable appetite for destruction. This is an image with extraordinary power.

Like the image of a packed pool party on a pandemic weekend. We presume those people are going to infect, and kill, others from their selfish behavior. We even presume that a number of them are carriers, currently infected, and we feel safe in this presumption because CoV-2’s infectiousness without symptoms was one of the first things we learned about it. The virus is what we accept, it’s the carriers’ behavior that’s unacceptable.

IV.

What I’m getting is how it’s easier (because it feels good morally) to attack the character and behavior of a person carrying a virus than it is to figure out how to live with a virus. And as a gay man who has watched his fellow gays get maligned globally for promiscuous behavior (especially during this pandemic), I’ve been reluctant to jump on the StayAtHome righteous bandwagon.

I think this is because I refuse to act politically in a public health crisis—and as I’ve said elsewhere on this blog, pushing to “Reopen America” before StayAtHome’s work is done is acting politically in a public health crisis. I’m staying at home. I’m wearing masks indoors. I’ve canceled my vacation travel. I don’t believe that humans have the right to shop or fill sports arenas during a public-health emergency, but I do believe they have a right to be near other humans: to fuck or party or tailgate or gossip or cuddle or play or drink or pray or whatever humans can’t happily do alone.

Gay activists demanded two things early in the spread of HIV: better research, and better health care. What kinds of sex can we more safely have and what kinds of sex are too risky? What does HIV do to the body and does it affect each host the same way? When we get sick, what can we expect? Where are treatment medications? Where is a cure or vaccine? How will you stop us from dying from this?

N.B.: They asked these of public health professionals. Reagan took years to even say the word AIDS. Politicians are not useful people to turn to in a pandemic. What this pandemic has shown us is that all the people who saw this coming and knew how best to handle it don’t worry about getting reelected.

Is why I’ve been happy to see newspapers run stories about what we might call Safer Socializing practices. Meeting couple-friends outside with masks? Sure, low risk. Indoor masked dance party with one shared bathroom? Big, big risk. Being the best bottom slut at the bathhouse? Big, big risk. Hooking up with a semi-regular fuckbud to relieve some stress. Less risk.

But how much risk?

V.

I don’t know how much risk. I don’t have any semi-regular fuckbuds. But I want to trust that those who do are doing the work of weighing their risks. I know this is naive. I know it’s hard to imagine that people filling Missouri pools or Florida beaches (or Los Angeles beaches, for that matter) are doing that work.

But I also know that people in different cultures have different cultural needs than I do. If this were a longer post, I could get into the reasons why closing public and private sex venues is an act of gay oppression that should be as illegal as closing every Baptist church, but instead I’ll end with a quick story.

Two weeks ago, on our weekly Madden-family FaceTime session, Mom appeared on the screen and immediately my sister noticed something different. “Did you get your hair done?” she asked, and Mom said “Yes” in the sheepish way where she doesn’t quite look at you (/the camera) and wishes immediately to change the subject. My sister shook her head. I’m sure I did too. Mom mentioned how her hairdresser wore a mask, and she sanitized everything, and overall she felt the risks were minimal.

“You don’t understand,” she said, “it’s about depression more than anything else.” Or maybe she said “self-esteem.” Whatever it was, the idea was that getting her hair done made her feel better during a time she hadn’t been feeling great, because who among us has? Mom gets her hair done every two weeks, and it had been two months. This is her culture. She’s also in her 70s and not in the best health, and I fear for what would happen if she got infected.

It’s very easy for me to shake my head and roll my eyes that Some People Put Vanity Over Their Own Health. But what do I know of other people? Better, I believe, to go with what the Times put on that iconic cover: “They were not simply names on a list. They were us.”