The whole country knew California had an election this week to recall the governor, an election that failed. The pundit wisdom is that Trumpism gave Newsom his victory, and given that a number of Californians I follow online didn’t seem to get vocally involved in anti-recall activism until after a far-right talkshow host became the leading replacement candidate, I imagine they might be right.

Though only 42% of voters turned out on Tuesday, or mailed in their ballots on time.

For me the message has always been: Don’t vote No because you fear the new guy, vote No because you love democracy, and this isn’t it. The rich people who paid enough money to gather enough signatures never had to make an argument that Newsom was unfit for the office. He broke no crimes. He committed no ethics violations. He just governed differently than they liked, and all they needed for a chance to replace him was the 1.5 million signatures they paid for—and if that seems like a high number to you, that’s equal only to 12% of the last gubernatorial electorate,[1] which is the required threshhold by which California automatically had to begin the process of setting up a recall election. Kansas, by comparison, requires signatures totaling 40% of the electorate.

It’s an enormous and costly process. Tuesday’s recall election cost California at least $276 million to run. If you want to know why that number is so high, I served as an inspector at a polling place on Eureka Street, and I will tell you what we had to do. Bonus: you’ll get to see what it means to hold a fair, functional, and accessible election. And extra bonus: you’ll hopefully see why we need to Vote No Again on 2022’s recall of three San Francisco school board members, and on the likely recall of our district attorney.

I. Preliminaries

Weeks before election day, I had to take a 90-minute online training in election procedures and policies, and answer a number of short quizzes correctly to show that I’d been paying attention. I’ve taken this training twice before, but that didn’t exempt me. Everyone needs to be retrained every year, not only because of subtle differences in procedures (no distancing requirements this time, e.g.), but because you forget. And we need poll workers who know how to process votes.

Then I had to schedule a 1-hour in-person training at City Hall to learn how to set up and take down both the Ballot Scanning Machine and the Ballot Marking Device (more on these later). Again, I had set up and taken down these machines thrice before, but everyone gets trained every year. Afterward, I received my polling place assignment, and my Inspector Bag, which contained all the ballots we’d need at the polling place.

The night or two before election day, I reached out to my fellow poll workers, to verify that they were ready to work on election day and answer any questions they had. Often it’s hard to get workers to commit—that is, usually there are last-minute changes to the team. I had a number of people who were unable to do their training in time or had a covid exposure, and in the end I ended up with two clerks. Running any polling place is a 4-person job, but we would have to make do.

II. The Setup

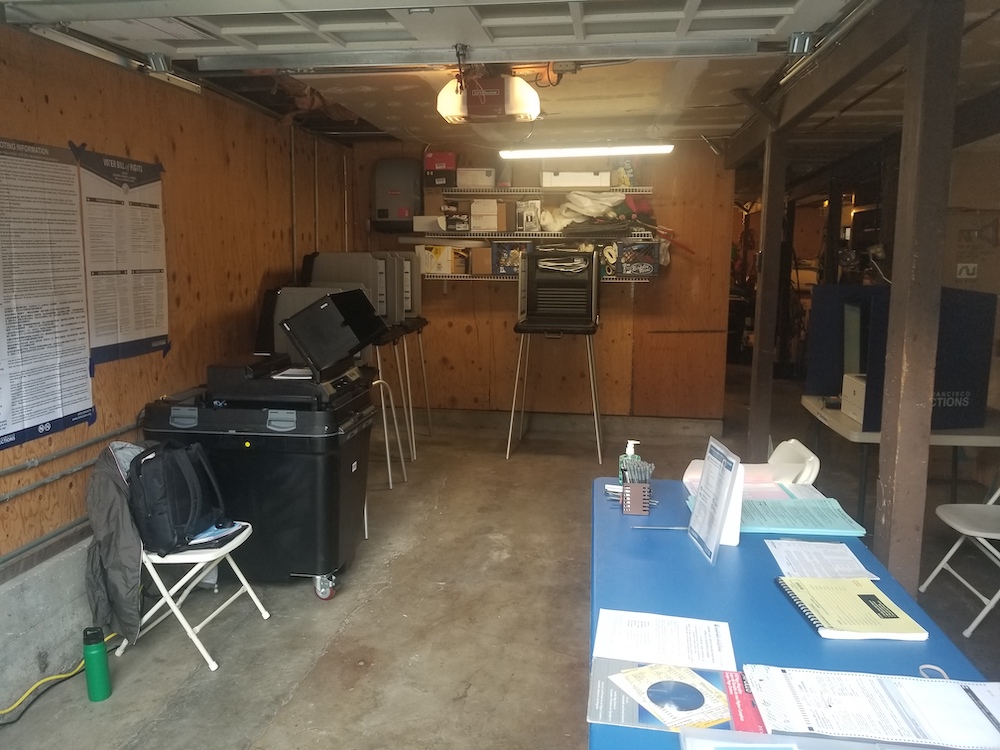

My polling place was a 6-minute drive away, and as the Inspector (which essentially means I’m head clerk) I had to be there at 5:45am, so I could sleep as late as 5. I arrived and found the owner of the house whose garage constituted our polling location chatting with one of our clerks; the other arrived shortly thereafter. In the garage were three folding tables, 6 folding chairs, and 6 folded-up voting booths (which in SF are essentially privacy-paneled desks on high stilts). There was the Ballot Scanning Machine, and the luggage-type bags that held the Ballot Marking Device and its printer. There was the red box where people would drop off their mailed ballots, which was filled with supplies for the greeting table, plus a kit of extension cords, masking tape, 3-prong outlet converters, and everything else we might need to get something like a garage in working order. Plus a bag of signage required by law. Plus a bag of informational supplies for the election table, also required.

We had about an hour to get all of that set up according to election laws and a site-specific diagram we’d been given by the San Francisco Dept of Elections. Polls opened at 7am. No matter what happened, we needed to open the polls at 7.

My job was to assign tasks to the other two clerks, while I used my Inspector credentials to get the machines running. The Ballot Scanning Machine is self-explanatory; it records the results and number of in-person votes by accepting the Scantron-style ballots voters filled out in their booths. It’s a touch screen that requires passwords and certain procedures to open the polls. The Ballot Marking Device is also a touch-screen thing with passwords and procedures. Its function is to allow those with disabilities preventing them from filling out a paper ballot to vote. There’s the touch screen. There’s audio for the vision impaired and a game controller–like device that can move a cursor around the screen. There’s a way to use a sip-puff device to vote. The setup is straightforward: plug everything in, connect the device to the printer, print a test page, open polls.

At 7am, I shouted “The polls are open!” to the street outside, which was empty of people. Here’s what our garage looked like:

III. Polls Are Open

Half the people who showed up just wanted to drop the ballot California mailed them into our sealed red box. The other half wanted to vote on a printed ballot and get it scanned and counted on-site. Nobody ever had to show an ID to do so. Maybe 1 in 5 voters would pull out an ID after we by law asked for their name and address, and we’d say, quickly, “No need to show ID!” One woman stopped and looked at me. “Oh that’s not okay. That’s gotta change.”

“Actually, there are a number of systems in place to verify this,” I said. “It works.”

“Really?” she asked, and it was a curious and surprised “Really?” not a skeptical one. Which is one of the lessons you learn quickly about the electorate when you work a polling place: everyone trusts and believes in us poll workers.

After I told her the election is safe and fair without IDs, I wondered whether that was true. Had I lied to her to stop her anti-democratic feelings? I thought about it, and it would be possible to commit election fraud if a number of very specific events happened in a specific order. If I wanted to vote twice in the same election, I would first need to know the name and address of a person registered to vote, and I would need to know where they voted. This is all online. I would need to make sure they didn’t already vote by mail, because if they did, as soon as I got to their polling place, the clerk would explain that the Dept of Elections already received my ballot, it’s listed right here in the roster, and so the only way I could vote there would be provisionally. You need to sign a provisional ballot, and you need to sign a mail-in ballot, and I think you need to sign a registration card, so in addition to all the above, I’d need to be able to forge the registered voter’s signature. If I could, then the Dept of Elections would need to decide whether to accept a mailed-in ballot or a day-of provisional ballot, and while I have my own ideas which of those to accept and reject I don’t know what their protocol is for this, but the point is that one of those ballots will be rejected. So maybe I myself have voted twice, but that’s still, in aggregate, one person one vote.

But what if the person I’m impersonating didn’t vote by mail? Well then I’d need to hope that either (a) I beat them to the polling place or (b) they decided not to vote at all. Again: the same forged signature issues are in place, as we need everyone to sign the roster proving they are who they say they are. And if (a) happens and the real voter shows up afterward, they would be told “You’ve already voted today,” which I imagine would be enough of a surprise that they’d produce ID proving they were who they were, in which case there’s a page where we can challenge any previous vote, and tell the Dept of Elections to reject the first one and count the second. (The CA Elections Code says that challenges should favor the challenged voter, i.e. the person insisting they haven’t already voted and are who they say they are.)

I get into all this to show how expensive, because thorough, fair elections are. And a healthy democracy works hard and spends money to make it easier for its citizens to vote. Easy registration procedures are part of this, but so is the fact that San Francisco has more than 500 polling places in the city. I think USF’s campus has 2 of them. Our voters on Tuesday kept saying, “Oh I just live around the corner.” I passed another garage polling place when I walked on my break to find some food. There were at least 3 and possibly 4 people at each of those polling places working to help voters vote.

At any rate, 2 of the 3 of us workers had to be in the garage from 7am to 8pm, which is the time when polls are open. (After a dead stretch between 7pm and 8pm, there’s always one guy who comes in with 5 minutes to spare.) It’s a long day of looking people up in the roster and getting them to sign their names, explaining the voting procedures, explaining why they have to vote a provisional ballot if they aren’t in the roster, voiding the mailed ballots they brought with them because they want to vote in-person, or because, as one guy explained, his toddler had drawn on it.

This blog post is boring because the work of this is probably boring. It’s knowing a lot of arcane laws about voting, but working a polling place is never boring. Well that’s a lie: we could go an hour without seeing anybody, and for stretches there’s nothing to do but sit in a garage with strangers. But almost everyone thanked us, just for doing what we were doing. And everyone was nice. One woman got an error message when feeding her ballot into the Ballot Scanning Machine, and the message said she’d “overvoted”—chosen too many candidates for a single race. We explained that she could either submit the ballot as is, or we could return the ballot and she would get a new one. “Oh, that’s okay,” she said. “We can just leave it.” And I said, “It’s very easy to give you a fresh ballot so that your votes are counted.” And she stopped and looked at me, and said, “Okay.”

She voted Yes on the recall, I couldn’t help notice when we voided the ballot. I was happy to help her do this.

I haven’t even mention the 3 elections officials that visited our polling place multiple times during the day. One was to check that we’d set everything up in a way that was accessible and adhered to election laws. We had not. Given the tightness of our garage, I’d decided to leave 3 of the 6 voting booths packed away in the back. But even though we never had close to 6 people voting at once, election law dictated that we provide this many booths, so this official helped us find a way to get them all up with enough space around them for anyone to maneuver. One guy came and checked our tech was operating okay, and then he came back hours later to check again. We weren’t on our own. These folks had 5 and sometimes 10 polling places to watch over, so do the math on how many people are working all day in San Francisco alone just to make sure elections are fair and functional. Now do the math for California, the most populous state in the country. It’s awe-some, when I think about how well we make democracy happen.

IV. Polls Close

This is always the worst part, because all you want to do is go home after what’s been a 14 hour day, but we need to verify all the votes cast, count all the remaining ballots, and do a number of checks on security systems, which involves 3 forms and a lot of accounting. And all the while we have to shut down the machines, take down tables and booths and signage, and on and on and it takes about an hour. Then we need to wait for two city officers (a transit cop and a sheriff cop) to come take away the ballots and the election results, which come from the Ballot Scanning Machine. It has a little register tape it spits out the vote tallies on, and we clerks have to sign it and tape a copy outside our polling place. (Did you know that about an hour after polls close you can walk around the city and see how your candidates did at each polling place?) It also has 2 memory cards I unlock from panels on the side and seal up in bags. And of course, there are the actual paper ballots that were put in the machine. So again: elections are fair. They are incredibly well run.

Usually we go home around 9: 30. So let’s call it a 16-hour day from when you leave the house to when you get home.

V. Recalling the Recall

I wasn’t going to be an inspector this time. I liked the idea of taking 2021 off (CA has no November election this year). But I started reading about suspicions of election fraud, and the pro-recall people coming out in a big numbers to stop any malfeasance, and I thought, Come at me, you fucks. Election fraud is a fantasy fueled by a feeling many of us have, regardless of our politics: other citizens can’t be trusted. Our government, made up of other citizens, who have formed systems by which we make democracy happen, can’t be trusted.

I don’t take election fraud fantasies personally because I’m a poll inspector. I take them personally because I’m a citizen.

San Francisco has another recall election coming up, likely in January or February, to possibly remove the three members of the School Board who’ve served long enough to be eligible to recall. (The rest started only in January.) SF requires signatures equal only to 10% of the electorate to trigger a recall. This, as you can imagine, is fucked and stupid, but here we are.

The pundits are quick to point out that this recall isn’t driven by Trumpism. (I’d argue otherwise.) This one’s not a power grab, this is direct democracy by angry parents who mostly vote Democrat (given where we are). Here’s a telling quote from Heather Knight’s Chronicle coverage (headline = “Opponents of S.F. school board recall say it’s fueled by Republicans. Tell that to its liberal backers”):

If you are angry at what your elected officials are doing, you don’t get to force a recall to fire them from their jobs. That’s what elections are for. And if only 10% of the electorate wants a recall, they don’t get to force the majority to vote. These are (or should be) basic tenets of democracy. What I’m afraid of is that people will see that this recall has this Gaybraham Lincoln asshole’s endorsement, and so (in San Francisco at least) think of it as a “good recall.”

There is no good recall, not with the undemocratically low standards California has set up.[2] I’ll point out here that the three members of the school board up for recall are up for reelection in November 2022, so we might need to have, city-wide, an estimated $7.2 million election on whether to oust people we could just not vote for 9 months later.

This is my point for this whole long post: With any recall election, it’s not about the outcome, it’s about the purpose, the cause. Have crimes been committed? Have ethics violations gone unpunished? Have our representatives failed in their duties to govern?[3] And most importantly: is an undemocratic method of removing them from office more important than letting democracy do that job?

To me, it never is. We all work too hard on democracy together to let a few rich people force recall elections to get their way. Please, please vote no on the recall(s) next year.

- Not 12% of the population, or even 12% of registered voters, 12% of all the people who voted for that race last time.↵

- Fortunately, after this failed recall, people are starting to think about changing the rules.↵

- School board recall folks have a case that they have, and I’ll leave it to you to decide if they do, but if you ask me they’re blaming people for a pandemic’s damages.↵

“If you are angry at what your elected officials are doing, you don’t get to force a recall to fire them from their jobs. That’s what elections are for.” <– this x 1000. I know we've been having this conversation off-line for some time now, but it can't be reiterated enough. Recall elections like this only undermine the regular electoral process and the assumptions underlying elections themselves – either by evidencing a lack of faith in the electorate or by, as you say, permitting the powerful to cynically game the outcome.

I agree with you about recalls, but on schools I’m actually team Gaybraham so we’ll have to disagree about that particular issue. (And no not the renaming of schools part. School renaming is fine by me.)

I really appreciate this post and didn’t find it boring at all. Huge, huge props to the effort you put into poll work. Talk about essential workers!