When I was a kid, as a private dare with myself, I’d sometimes stop and picture being dead. I’d close my eyes, because the dead couldn’t see, and imagine eternity. What I saw was a conscious void, almost like floating through space in a body that couldn’t move, but in this fantasy my soul lived on to watch itself, forever. I pictured having to not just conceive eternity, but continually face it. A thousand years of absolute black stillness, then a million years after that. My heart would start racing and I’d run off to distract myself from such thoughts. When I was a kid, I feared death more than anything.

I’m still afraid to die, but the fear now hovers around regret. I’m afraid to die before I finish this book, before I see the parts of the world N & I want to see together, etc., but I’m more afraid to look backward at the moment of death and see myself at the end of a story about a coward. Or a tyrant. Or a miser of his emotions.

Avoiding that regret takes a certain serenity of mind re the complex mess of living a long life, but it seems also to task me with sowing the right seeds in this present. I am—we all are—right now living the very life we’ll one day see from the perspective of its end, and so what exactly are we making? And more importantly: how can we live the life that pleases us now and will also please us later?

*

A couple weeks back I wrote about compassionate hedonism. That’s not what all this is about exactly, but I do think I’m talking about a focus on maximizing pleasures now without much concern for long-term effects (of, say, drinking or being yourself). Talk of life’s end brings to mind the popular obsession with longevity. I saw Death Becomes Her early in life (maybe even in the theater), so I know from the dangers of focusing on quantity of life over quality, and it’s almost not worth writing about the glut of articles online with headlines like These 3 Lifestyle Changes Will Add Months to Your Life. Fearing death all those years, I read every such article I came across, and spent the next week or so consciously adding more walnuts to my diet, or trying to remember to sit and breathe pranic-ly for 5 minutes.

I didn’t necessarily need to live to see 100, but I knew I didn’t want to die in my 80s. To die in my 80s felt like quitting the race before I reached the finish line, that I’d done too poor a job of pacing myself, and then having to watch others continue on without me. I’ve noticed in the last year maybe that I’ve stopped thinking this way, dropped the whole notion of a target number all together. I want instead to enjoy my time running, to belabor this race metaphor. I think I’d be okay dying in my 80s, my 70s, my 60s even, so long as I was dying without regret.

*

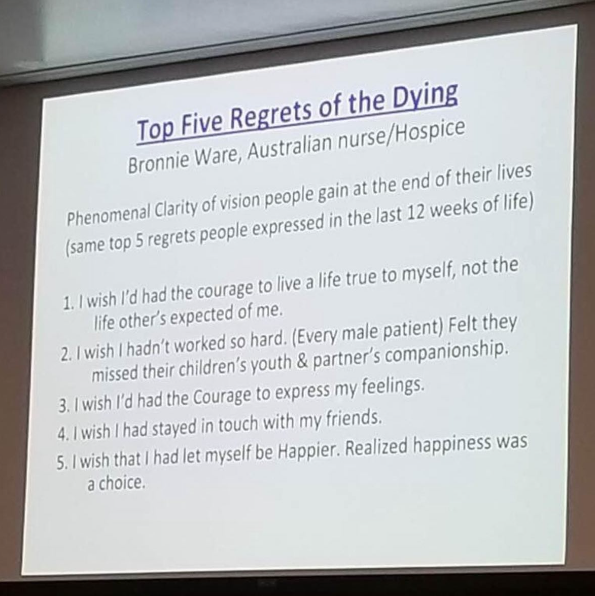

It’s with all these notions that I was a quick liker of this recent Instagram post I found in my feed:

I’ll type it out (with edits) for better legibility:

Top Five Regrets of the Dying

Bronnie Ware, Australian nursePhenomenal clarity of vision people gain at the end of their lives (same top 5 regrets people expressed in the last 12 weeks of life)

1. I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.

2. I wish I hadn’t worked so hard. (Every male patient; felt they missed their children’s youth and partner’s companionship.)

3. I wish I’d had the courage to express my feelings.

4. I wish I’d stayed in touch with my friends.

5. I wish that I’d let myself be happier. (Realized happiness was a choice.)

I have some cynicisms to work through before I get into how this list moved me. One’s about this ‘phenomenal clarity of vision’. Ware wrote a book about these regrets, one I should probably read, but much of this sounds like a just-so story about death and dying—that deathbeds are a site of magical wisdoms. I haven’t sat by anyone’s deathbed, and I’m of course not a hospice nurse, but clarity of mind doesn’t seem to be a salient feature in the final weeks of a person’s life. (I’m thinking of those who die at a very old age, and all the levels of cognitive decline that attend such a death, but maybe Ware’s book’s wisdoms come from folks dying at all ages.)

I also want to dismiss the implication that happiness is a choice, another just-so story we like to tell about happiness. Why should that emotion get this special status apart from the others? Do we tell people that fear is a choice, or anger? I know so little about emotions, but whether or not we sort them into ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ ones, it seems like a total lie to imply that a successful life involves learning how to opt out of some in favor of others. Fear comes to you in a blink. People make you angry in how they treat you. Just imagine choosing never to feel surprise. (Or only to.) As this great recent New Yorker article unpacks, our emotions are not created or even experienced inside us, in isolation, but rather are far more external and socially constructed than we tend to see. Likely this bit about choosing happiness is meant to suggest silver linings, or mindfulness practices. Taking time in the thick of life’s messes and disappointments to reconnect with, or see anew, the parts of it that fill us with joy, however small or short-lived.

*

As I said, I was moved by this list the way Scrooge was moved by the sight of his own grave. I took it as a warning, with the relief in my heart that it didn’t seem to be too late. Act now was the general idea. Check in with yourself on how true these are for you. I don’t live a life true to myself, because I’ve convinced myself that myself as I am—fiercely boundaried, caustically angry, endlessly horny, manic and spastic, talking to himself in silly voices, picking his nose amorously, quickly disappointed by virtuousness (I won’t go on)—makes me unacceptable to others.[*]

I do stay in touch with my friends. I Zoomed with 2 middle school friends on Wednesday and will Zoom with 2 college friends tonight. We do this like clockwork. It has changed the quality of my life immensely, and I love my friends so much I’d do anything to keep them in my life.

At any rate, as soon as I saw the post I started thinking about how to teach these—not, probably, in my own classes. But as a teacher, I have kneejerk reactions against Life Lessons, which often read more like learning outcomes than actual lessons. Any time you share something you’ve learned, you tell someone the end of a story they haven’t themselves lived through, and it’s likely a story you can’t reconstruct. What steps did you go through to come to understand that thing you know, and can you be sure those steps are translatable to another person’s lived experience?

Teaching is many things, but one of its arts is learning how to find (or, often, fabricate) that story from not-knowing to knowing.

So how do you teach choosing happiness, if happiness is indeed a choice? How do you teach gauging the limits of hard work? Note how much there is to teach in these stated regrets. What is courage, exactly, and how does it differ from bravery, or derring-do? How do you recognize courage within yourself, and then how do you cultivate it? How do you know when to use it? And then after the courage unit’s learning is achieved, it’s time to go on to feelings. What are they, exactly, how do you discern among them, etc. etc.

Finally, you can move on to the expression of feeling, which has been much of the focus of my therapy sessions for the last 7 years or so. Even understanding why this is unbelievably hard for me is unbelievably hard. I think much of the learning has been unlearning, undoing; my guess is that we as children don’t have trouble expressing anything, but somehow pick up over time habits of nondisclosure, or of shutting up, shutting down, burying feelings out of some disregard for them, or in some faith that the situation will improve with our silence.

Regardless of how I learned what I learned, I’m in therapy to unlearn it, because the life I’m preventing myself from living by not expressing my feelings has become more and more tangible and manifest. I can see it, just over there, almost like through a tall chainlink fence. And I also feel, at 44, that the time I have is starting to run out, and one day I’ll no longer have what it takes to climb over there.

Which returns me to a final cynicism about these regrets: is it even possible to die without them? Living a life without regret seems to be as possible as living a life without sadness, or anger, or even happiness. None of these are states to achieve, but storms that pass through us multiple times a day. Like ‘choosing to be happy’, we might also allow the dying to choose to ignore the times they, as human beings, didn’t live up to our ideals. Who always can?

- I know I said I wouldn’t go on, but the question naturally follows: Why not just be yourself all the time? And the answer that comes to mind is the same answer I always had at the ready when I asked myself Why not just be gay? I’ll lose everyone. As in some sudden exodus. And it’s worth remembering how that didn’t happen. Indeed, I didn’t lose anyone.↵