Dec 5, 2018 | Books, Queers |

[Full disclosure: Ari teaches with me in the MFA Program at the University of San Francisco. He signed my copy of this book.]

[Full disclosure: Ari teaches with me in the MFA Program at the University of San Francisco. He signed my copy of this book.]

“Mostly a name feels like the crappy overhang I huddle under / while rain skims the front of me.”

This is how one poem late in Ari’s debut collection starts, and I loved it because it’s so unlike how I feel. My name I did the good work to grow into, and any changes I made to it—going from David to Dave around 1992—I did because it felt faster, easier.

But such is the luck of being assigned at birth the gender I feel inside. From the position of the trans body Ari maps so movingly in this book, names mean more, and come packaged with more. “I admit it keeps me visible,” the above poem continues, “the agreement to call this that.”

I’m not a strong reader of poetry. It charges a part of my brain I don’t often exercise, a darker part perhaps that makes me feel uncomfortable. Perhaps this is why I was drawn to the darker corners of Ari’s poems. “The Feeling” starts with a red cloud that comes annually up the Aegean—Ari’s people are Greek—and “covers the buildings, the cars, / in a fine red film of dust from elsewhere.” But soon the poem shifts to the moon, and then to the incarcerated, and throughout the field of war on which nations play.

It’s an unstable place, and this is a book that felt drawn to, or driven to understand, unstable places:

I can say moon and tree and fox and river,

or me and you, or love and stutter,

but I can mean corporation I can mean police.

I can mean surveillance,

or that the moon is a prison, it is daytime,

and in daytime no one sees the moon.

The poem reads like an essay with images that arrest me, which is basically everything I ask a poem to be. “This is not our poem,” it ends. “The poem has been privatized. Its flag will be a red feeling.”

I also loved “Hog”, late in the book, which is a kind of bestial/motorcycle/leather fantasy that reminded me of Samuel R. Delany’s novel Hogg. Ari’s landscape here is blurred, or maybe tilled up is the better metaphor: “What’s a hog / but gleam of handlebars, leather, that roar speeding by. / The scared parts dressed up tough, saying / ah come on let’s go chop up the wind.”

“Narrative” might be the closest the book gets to a clear portrait of the young trans body before coming out, and it’s so good I want to just quote all of it, but instead I’ll point you to its initial publication in Verse Daily and quote this part I love the most. It’s one of my favorite images I’ve read all year:

In Illinois I tried to build a kind of Midwestern

girlhood that failed and failed

into the shape of a flute

I played only high notes on.

What else? Oh, what a joy it was to read this part from “Handshake”! I felt heard, understood. I felt like I could find the friends I need if only I could open up about the honest parts of myself I feel it would be better to keep inside, lest I scare off potential friends:

I know I'd prefer to misbehave

continuously. Any squirrel gets what I mean—anarchic revelry,

refusing to ever be still, such keenness.

They own no tree so they all own all of them.

I'd like to flick my tail too whenever I want as if to say WHAT.

But at any moment I'm wherever someone puts me—

then change my mind. I'll pick a side

when I need to

You can buy Anybody here.

Nov 15, 2018 | Books, Queers, Reviews |

Nick is a dear friend. Fellow Nebraska alum (though later), fellow Sewanee alum (we were suitemates). You’re not going to get an objective review here of a collection that is gorgeous in its compassion, and in the compassion it made me feel for its characters.

Nick is a dear friend. Fellow Nebraska alum (though later), fellow Sewanee alum (we were suitemates). You’re not going to get an objective review here of a collection that is gorgeous in its compassion, and in the compassion it made me feel for its characters.

Maybe it’s not compassion I want to write about, because the OAD has it as “sympathetic pity and concern for the sufferings or misfortunes of others,” and that’s not what I felt reading these stories. But I don’t want to write about empathy because I’m bored of talking about empathy in fiction.

Let’s try this: Nick’s writing made me feel feelings toward made-up people I have a very hard time feeling in my waking day-to-day life.

I’ll start with his final story, and I think his best: “The Last of His Kind”. It’s about a family in Mississippi, a somewhat bare-bones family of son, dad, and grandmother. The inciting event is a woodpecker hammering away at the house at early hours, which bird turns out to be the last Ivory-Billed Woodpecker (hence the title). Family lore has it they’re under the spell of a Choctaw curse, and it’s the task of the son, Henry, task to try to rid them of it.

The story comes at the end of the book’s second section, which is a story cycle centered on the life of the dad, Forney, and much of its wonderfulness comes from Nick’s skillful way of tapping into the histories of these characters we’ve been dipping into over the past 100 pages. Many of the passages felt buoyed by the culmination of lives I’d seen so much of.

The wonderfulness also comes from the wide range Nick allows himself in the POV, dipping even into the woodpecker at times. Here’s a moment, for instance, I loved:

She turns the record over, and George Jones’s duet with Tammy Wynette, called “Golden Ring,” fills up the house. MeMaw sings over the Wynette parts, her voice and achy. She imagines the little bird inside her being nudged awake. She sings and sings, her throat opening. She pictures the bird clawing up her rib cage one curved bone at a time, then, seeing light, flitting out of her mouth hole and soaring away. Oh, to be a bird! To shed this wrinkly skin and become all feather and claw. Nearly reptilian.

The boy, becoming braver, swigs the beer. Some of it fizzes down his chin, and MeMaw roars with delight. He wipes his face and comes in close, his face inches from hers, his eyes large and brown.

“I thought birds fly south for the winter. Why don’t it fly south?”

MeMaw takes the boy’s face in her hands and kisses it. “Because, baby, we are the South.”

I loved “mouth hole”, but mostly I loved the simple grace here, and how much love emanates from the scene. It’s one of Nick’s gifts. He’s got a heart bigger than anyone’s, and a vocab more colorful than a Cezanne.

You can buy Sweet & Low here.

Nov 2, 2018 | Announcements, Books, Queers |

Welcome back. I took some time off to redesign the website, and I want up front to thank Beth Sullivan for the outstanding (and very patient) work she did on it. You should hire her.

While things were under construction, I was keeping up with my year of queer reading. To catch you up, here’s the list since Humiliation:

- Are You My Mother? – Alison Bechdel

- Andy Warhol – Wayne Koestenbaum

- Zami: A New Spelling of My Name – Audre Lorde

- Caroline, or Change – Tony Kushner

- Less – Andrew Sean Greer

- The Fact of a Body: A Murder and a Memoir – Alexandria Marzano-Lesnevich

- How to Write an Autobiographical Novel: Essays – Alexander Chee

- Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl – Carrie Brownstein

- Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl – Andrew Lawlor

- Abandon Me: Memoirs – Melissa Febos

I’m also a slow reader. Expect a post or two about these once I’m back from the NonfictioNow conference. I’m happy and relieved to have this space back to work out ideas about books and queers and teaching and guitar tabs and whatever messes I get into.

Jan 29, 2018 | Books, Queers |

It’s unconscionable that it’s taken me so long to discover Wayne Koestenbaum’s essays: he’s writing in the precise mix of intellectual, critical, and personal that I aim for. A role model. I read his My 1980’s and Other Essays, a kind of omnibus of recent shorter pieces, earlier in the month, and it made me hungry for something longform. Humiliation is a booklength essay on that topic in the shape of 11 fugues.

It’s unconscionable that it’s taken me so long to discover Wayne Koestenbaum’s essays: he’s writing in the precise mix of intellectual, critical, and personal that I aim for. A role model. I read his My 1980’s and Other Essays, a kind of omnibus of recent shorter pieces, earlier in the month, and it made me hungry for something longform. Humiliation is a booklength essay on that topic in the shape of 11 fugues.

It’s the sort of book I hope this book I’m writing might turn out like.

Here are just two of the things I loved (of so much in the book worth loving, like Koestenbaum’s writing on shame and the body and the queer body and porn and desire). One is what he calls “the Jim Crow Gaze”:

The eyes of a white person, a white supremacist, a bigot, living in a state of apartheid, looking at a black person (please remember that “white” and “black” aren’t eternally fixed terms): this intolerant gaze contains coldness, deadness, nonrecognition. This gaze doesn’t see a person; it sees a scab, an offense, a spot of absence.

It’s a useful term for a look I’ve seen on faces my whole life. A face we see every day on the president. A look I imagine I’ve worn more than once.

The other thing is the entirety of page 171, from the book’s final fugue, listing humiliations from Koestenbaum’s past:

23.I gave two of my poetry books, warmly inscribed, to a major poet. A few years later, my proteg? told me that she’d found those very copies, with their embarrassingly effusive inscriptions, at a used-book store.

24.At an academic conference, a student stood up, during the question-and-answer period, and accused me of assigning only white writers in a seminar he’d taken with me. Some audience members, appreciating the student’s bravery, applauded.

25.After the panel ended, a colleague?whom I considered culturally conservative?came up to hug me. I told him not to hug me right now; I didn’t want my revolutionary accusers to see me collaborating with privileged humanists.

26.The next day, I called up this colleague and asked him out to lunch. At first he refused. He said, “You shunned me.” The next day, at the cafe, he told me about a lifetime of being shunned.

27.Later, this colleague died of AIDS. I didn’t visit him in the hospital.

This litany of humiliations piled on each other makes me feel terrible. I feel Koestenbaum’s humiliation not just for having been an unsavory person, but for recounting these humiliations on the page. (This feeling of mine he expects and accounts for and speaks to throughout the book.) It’s so brave, which is a word I’ve tended to hate applying to essays.

Lately, I’ve been auto-sending a tweet each morning asking for suggestions of Twitter accounts that intentionally embarrass themselves or don’t try to appear likable or admirable or aggrieved. None have come in. Unsurprisingly, the only suggestions I do get are of parody accounts, or folks tweeting as some kind of funny character.

I read Humiliation, especially its final fugue, and trying to imagine it as a series of tweets I find myself dumb. My mind blank. To be a whole person online feels almost anatomically impossible, righteousness inhering to that experience as grammar does to a sentence. These days I’m seeing any such denial or avoidance of my embarrassments and private humiliating miseries to be a kind of self-treason.

Jan 26, 2018 | Books, Queers |

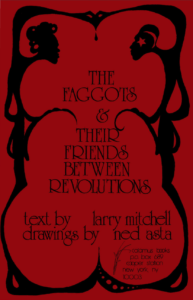

A new favorite. I didn’t know that all my life I’d been looking for a fable about queers loving and working together as they prepare to destroy the patriarchy. Or “the men” in Mitchell’s parlance:

A new favorite. I didn’t know that all my life I’d been looking for a fable about queers loving and working together as they prepare to destroy the patriarchy. Or “the men” in Mitchell’s parlance:

The first revolutions destroyed the great cultures of the women. Once the men triumphed, all that was other from them was considered inferior and therefore worthy only of abuse and contempt and extinction. Stories told of these times are of heroic action and terrifying defeat and silent waiting. Stories told of these times make the faggots and their friends weep.

The second revolutions made many of the people less poor and a small group of men without color very rich. With craftiness and wit the faggots and their friends are able to live in this time, some in comfort and some in defiance. The men remain enchanted by plunder and destruction. The men are deceived easily and so the faggots and their friends have nearly enough to eat and more than enough time to think about what it means to be alive as the third revolutions are beginning.

It’s a short book. Over the course of it, the faggots and their friends help each other stay alive and sane in Ramrod, a place run by the men. These friends include the women, the [drag] queens, the [radical] fairies, the faggatinas and the dykelets. Even the “queer men” who dress and walk among the men, “using all the tricks their fathers taught them” and at night go out and cruise the faggots.

One of the beautiful things about this book, which is full of beauty and wisdom and even pretty line drawings, is how generous it is with its spirit. It is easy as an out and proud faggot to hate on the closeted “queer men” in this book. I’ve done it myself: big vocal public anger at Larry Craig types who work to protect and maintain straight power, and then try to also reap the joys of queer sex.

You don’t get to have both unless everyone gets to have both. You pricks should be locked up for life.

Mitchell, as I’ve said, is more generous. Here’s how he ends the page on the queer men:

It’s the most beautiful book I’ve read about solidarity.

That it’s a book everyone should read doesn’t, probably, go without saying. Maybe isn’t readily apparent. If I’m making it seem like this book (from 1977 and out of print, but any easy googling will turn up a PDF) isn’t for you straight friends of us faggots, if I’m making it seem like something niche, or a relic, know that this book gave me the clearest lesson on what the patriarchy is, at heart, and not just why but how to fight it.

I’ll leave you with one more bit to inspire you, one I’m planning to hang over my desk at work:

Jan 20, 2018 | Books, Queers |

Abandoned halfway through. This book is Not For Me. I think I failed to take its title literally enough: this is a how-to book for folks between their quarter- and mid-life crises. If All Advice Is Autobiographical, this book is a memoir, but one directed at a You I couldn’t quite step into:

Abandoned halfway through. This book is Not For Me. I think I failed to take its title literally enough: this is a how-to book for folks between their quarter- and mid-life crises. If All Advice Is Autobiographical, this book is a memoir, but one directed at a You I couldn’t quite step into:

Breakups make me feel old and haggard, all used up. Getting a new hairdo or a shot of Botox lifts me out of dumps. Even a mani-pedi and an eyebrow wax remind me to take care of myself?an outward manifestation of all the inner self-care breakups require of you, and a continuation of the declaration of self-love that you made when you dumped that fool. Oh, wait?the fool dumped you? As we say in 12-step, rejection is God’s protection! The Universe is looking out for you by taking away someone who was bringing you down. Give thanks by getting a facial.

What makes this Not For Me has little to do with gender (I like mani-pedis and restorative skincare treatments). It’s got a little more, perhaps, to do with age, but mostly it has to do with my looking for wisdom these days beyond 12-step bromides and This Worked For Me So It’ll Totally Work For You advice. But here’s where I’m trying to take this post: I can recall a time when I would’ve finished this book and set it aside a satisfied customer. Tea’s book’s being Not For Me is all about me, not her book.

Reading it brought me back to my first term teaching at USF. I had a student who wrote flash essays in this Tea-ish/How-To vein, specifically about how the reader might go about self-treating their depression without needing drugs or therapy. Self-care tips. Streetwise, This Worked For Me anecdotes. Assumptions that the reader’s life/background/belief system were in line with the author’s.

I was a shrewd, ungenerous reader of this work, aiming in my feedback to bring it all around to what I knew as Classic, Universal Essay Form: lengthen and enrich the structures, deploy more psychic distance between the narrator- and character-selves, etc. I wrote honest marginalia about how the You being spoken to was not me and was presuming things about me I couldn’t agree with.

The student protested: maybe I was reading it wrong, or unfamiliar with the style.

I counter-protested: how else can I help you but by reading this as I am, and gearing my feedback/revisions toward The General Reader?

Reading Tea, I saw at last an example of how I was wrong. If pushed in that classroom to describe The General Reader, I imagine I’d describe a man with a background and reading history closely aligned to my own. It is clear on every page of Tea’s book that whatever her notion of The General Reader might be, it’s not a 40-year-old professor who stays mostly at home and distrusts even the slightest interest in fashion and material objects.

The General Reader doesn’t exist. Not universally. It’s something I always try to keep in mind in the classroom: how is this work asking to be read? What do I know of the writing process (not The Essay Form) that can help this student see their work more deeply and develop it to the end.

I don’t know what I would do if handed Tea’s book in a workshop, but I know I wouldn’t do or say anything without listening to her first about what the work is, to her, and where she wants to go with it.

[Full disclosure: Ari teaches with me in the MFA Program at the University of San Francisco. He signed my copy of this book.]

[Full disclosure: Ari teaches with me in the MFA Program at the University of San Francisco. He signed my copy of this book.]

Abandoned halfway through. This book is Not For Me. I think I failed to take its title literally enough: this is a how-to book for folks between their quarter- and mid-life crises. If All Advice Is Autobiographical, this book is a memoir, but one directed at a You I couldn’t quite step into:

Abandoned halfway through. This book is Not For Me. I think I failed to take its title literally enough: this is a how-to book for folks between their quarter- and mid-life crises. If All Advice Is Autobiographical, this book is a memoir, but one directed at a You I couldn’t quite step into: